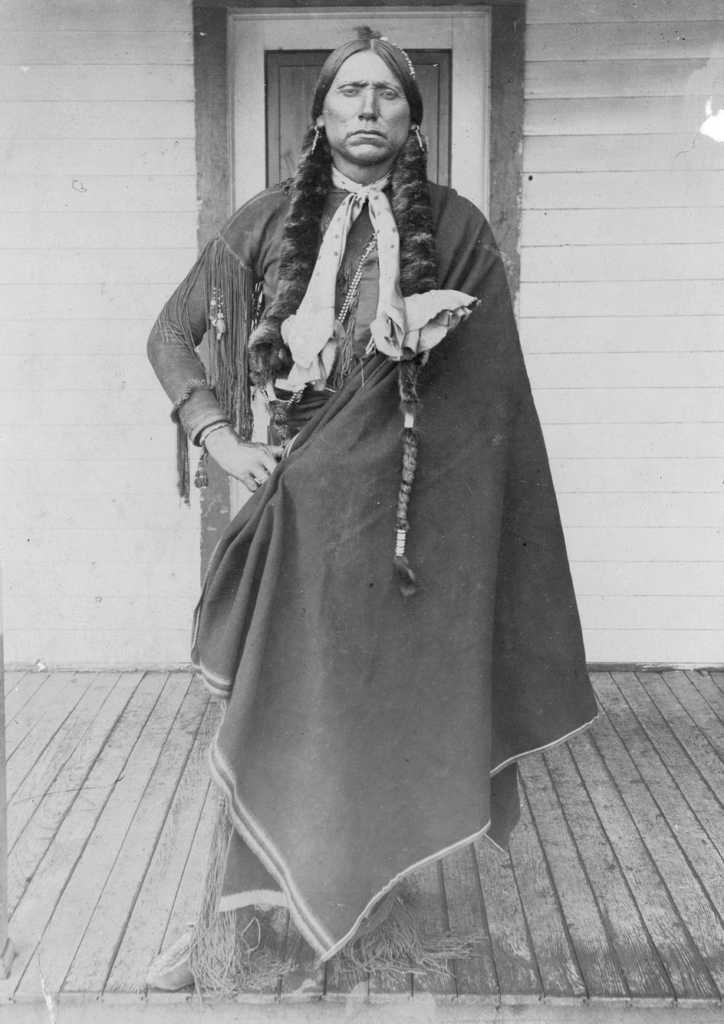

Peta Nocona, Lone Wanderer

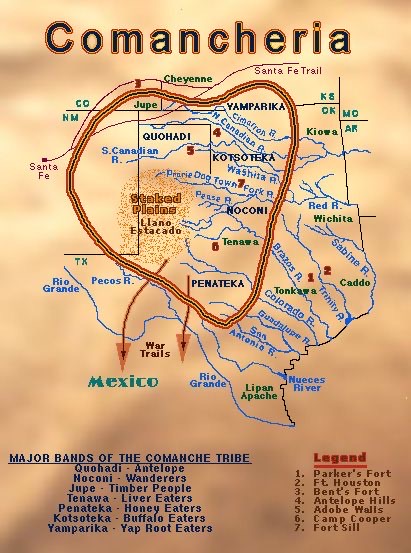

Chief Peta Nocona, born around 1820, was Chief of the Nokoni Comanche tribe during the 1860’s in Texas. He and his wife, Cynthia Ann Parker, were the parents of Quanah, Chief of the Comanches also known as the “Last War Chief of the Comanche”. Peta Nocona was a constant role model for son Quanah. Chief Nocona was a tremendous leader and know as the protector of the Buffalo. During his time as Chief he led the Nokoni Comanche tribe during the Texas-Indian wars. In response to the Council House Fight in San Antonio, Peta Nocona also led a Comanche raid on the Texas town on Linnville in 1840. Many believe his Nokoni tribe traveled just west of San Antonio down what is now Hondo Creek to get to Linnville. Wikipedia references it as the Great Raid of 1840. The rangers caught up with the Comanche tribe after the Sack at Linnville and had one of the historic fights between the Texas Rangers and the Comanches at the Battle of Plum Creek. Peta had just left the Comanche caravan before the Battle of Plum Creek had begun.

Chief Peta Nocona, born around 1820, was Chief of the Nokoni Comanche tribe during the 1860’s in Texas. He and his wife, Cynthia Ann Parker, were the parents of Quanah, Chief of the Comanches also known as the “Last War Chief of the Comanche”. Peta Nocona was a constant role model for son Quanah. Chief Nocona was a tremendous leader and know as the protector of the Buffalo. During his time as Chief he led the Nokoni Comanche tribe during the Texas-Indian wars. In response to the Council House Fight in San Antonio, Peta Nocona also led a Comanche raid on the Texas town on Linnville in 1840. Many believe his Nokoni tribe traveled just west of San Antonio down what is now Hondo Creek to get to Linnville. Wikipedia references it as the Great Raid of 1840. The rangers caught up with the Comanche tribe after the Sack at Linnville and had one of the historic fights between the Texas Rangers and the Comanches at the Battle of Plum Creek. Peta had just left the Comanche caravan before the Battle of Plum Creek had begun.

While it was rumored that he had been killed in a raid at Pease river by Sul Ross, his wife Cynthia Ann Parker said that he died years later from old wounds of an Apache attack.

The city of Nocona, Texas is named after him.

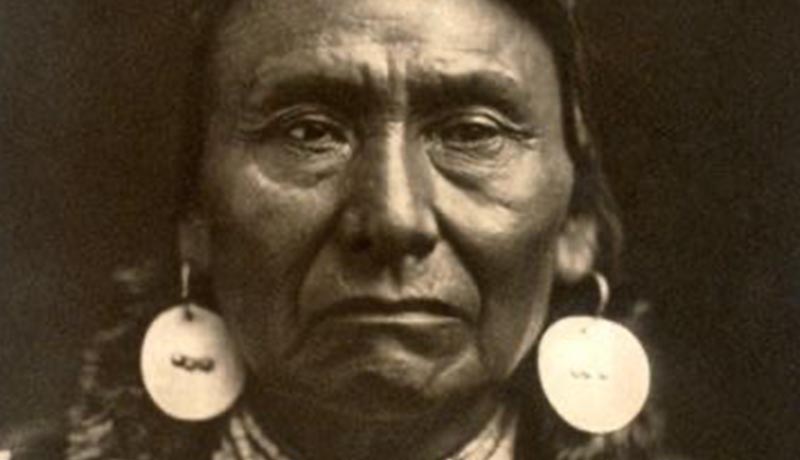

Quanah Parker

Quanah Parker, greatly influenced by his father, became the ware leader of the Quahadi (“Antelope”) band of the Comanche Nation. He was never elected chief by his people but was appointed by the Federal Government as principal chief of the entire Comanche Nation. He became a primary emissary of the Southwest indigenous Americans to the United States legislature. Outside of representing the entire Comanche Nation, Quanah gained wealth as a rancher, settling near Cache, Oklahoma. It is thought that through investments, he possibly became the wealthiest American Indian during is time. Towards the end of his life, he was elected Deputy Sheriff of Lawton in 1902. He was so well known and respected that President Theodore Roosevelt often visited him and would go on hunting trips together.

Additional Materials:

There a have been numerous books written about Peta Nocona and his son Quanah Parker. If you wish to learn more, below is a list of some of the most popular.

Empire of the Summer Moon: Quanah Parker and the Rise and Fall of the Comanches, the Most Powerful Indian Tribe in American History By: S. C. Gwynne

The Last Comanche Chief: The Life and Times of Quanah Parker By: Bill Neeley,

Quanah Parker, Last Chief of the Comanches: A Study in Southwestern Frontier History By: Clyde L. and Grace Jackson

United States – Comanche Relations: The Reservation Years By: William T. Hagan

Quanah Parker; Comanche Chief By: William T. Hagan